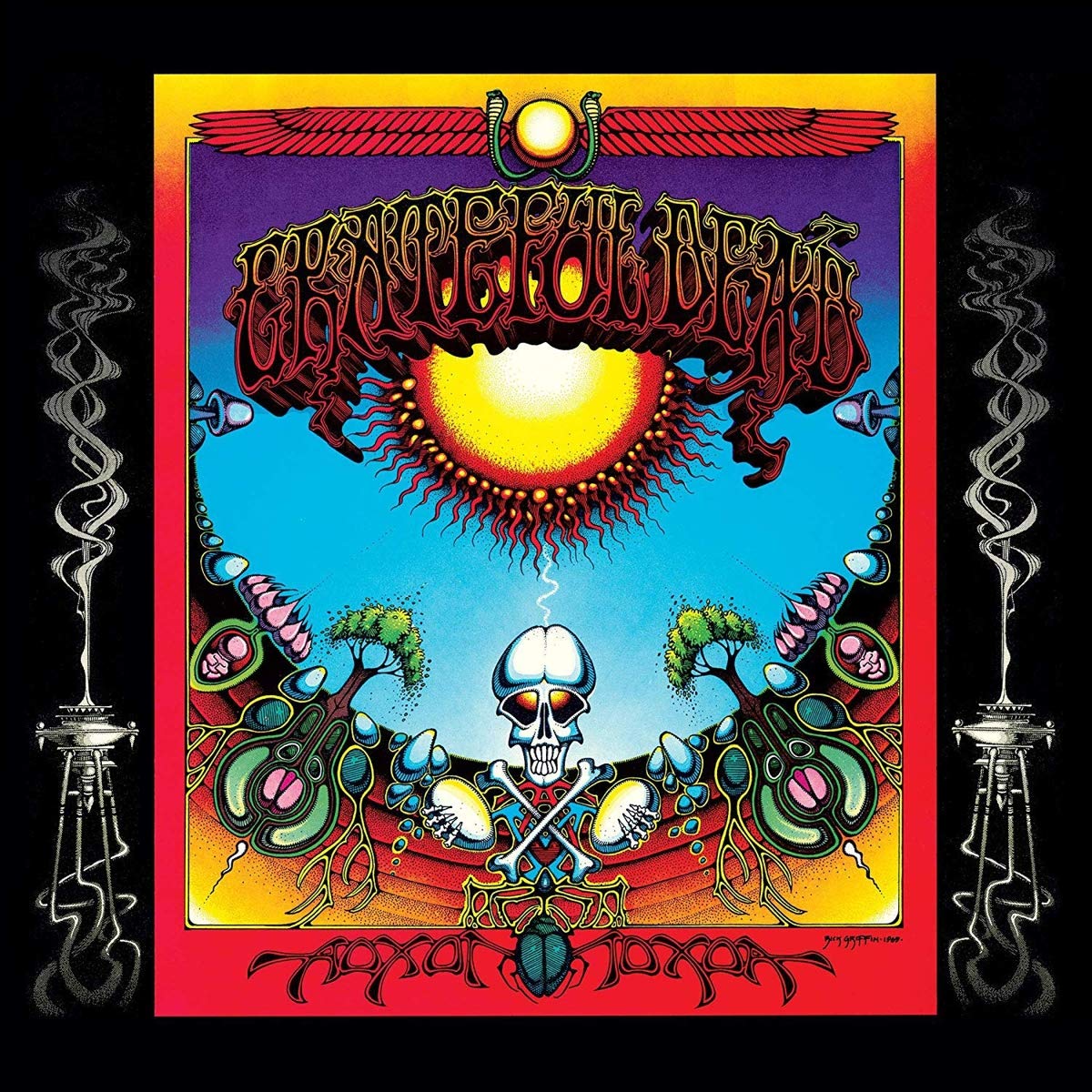

Nearly synonymous with the term “psychedelic,” the Grateful Dead reached their true peak of psychedelia on their third album, 1969’s Aoxomoxoa. The band had already begun work on an initial recording of the album when they gained access to the new technology of 16-track recording, doubling the number of individual tracks they’d used on their last album. Fueled by acid and keeping pace with the quickly changing hippie subculture of the late ’60s, the band went wild with this newfound sonic freedom. The exploratory jamming and rough-edged blues-rock of their live shows were ornamented with overdubbed choirs, electronic sound effects, and layers of processed vocal harmonies. Rudimentary experimental production took the band’s already-trippy approach and amplified it with generously applied effects and jarring edits. In their most straightforward songs, Aoxomoxoa’s ambitious production isn’t as noticeable. Gelatinous rockers like “Cosmic Charlie” and “St. Stephen” showcase Jerry Garcia’s spindly guitar leads and the band’s dusty vocal harmonies clearly before detouring into wild studio experiments. Though the studio mix of “China Cat Sunflower” sounds like the different instruments are floating in space, trying to connect from distant individual planets, the core of the song still comes through, and this number would become a live favorite for the rest of the band’s lengthy run.

This was the first album where the band brought on lyricist Robert Hunter, who would go on to pen some of the band’s best-loved lyrics. The early glimpses of the Hunter/Garcia partnership that come through on the bluegrass-inflected “Dupree’s Diamond Blues” or the mellow ballad “Rosemary” foreshadowed the complete shift to gentle Americana the band would make on their next studio outing, 1970’s masterful Workingman’s Dead. The overly experimental production could sometimes obscure the musical ideas, as distorted vocals clashed with acoustic instruments or multiple drum tracks ping-ponged across the stereo field. The eight-minute epic “What’s Become of the Baby” was the most glaring example of the album’s ungrounded production aesthetic, reaching an almost musique concrète level of weirdness with random electronic sounds and choppy effects swarming on Garcia’s isolated vocal tracks.

Aoxomoxoa was so out there that the band themselves had second thoughts, returning in 1971 to remix the album in full. The new mix dialed back some of the wilder moments and added clarity, but these eight songs would remain the most adventurous, confusing, and over-the-top productions the band would record. Aoxomoxoa is a prime example of the Grateful Dead’s difficult relationship with the recording studio, which would take different forms throughout their long, strange trip. Even leaning wholeheartedly into all the available bells and whistles, the band couldn’t quite capture with Aoxomoxoa the depths of cosmic wonder they tapped into organically every time they took the stage. Not without its excellent moments, the album is more a document of late-’60s studio experimentation than a huge step in any sustained path for the band. -All Music Guide