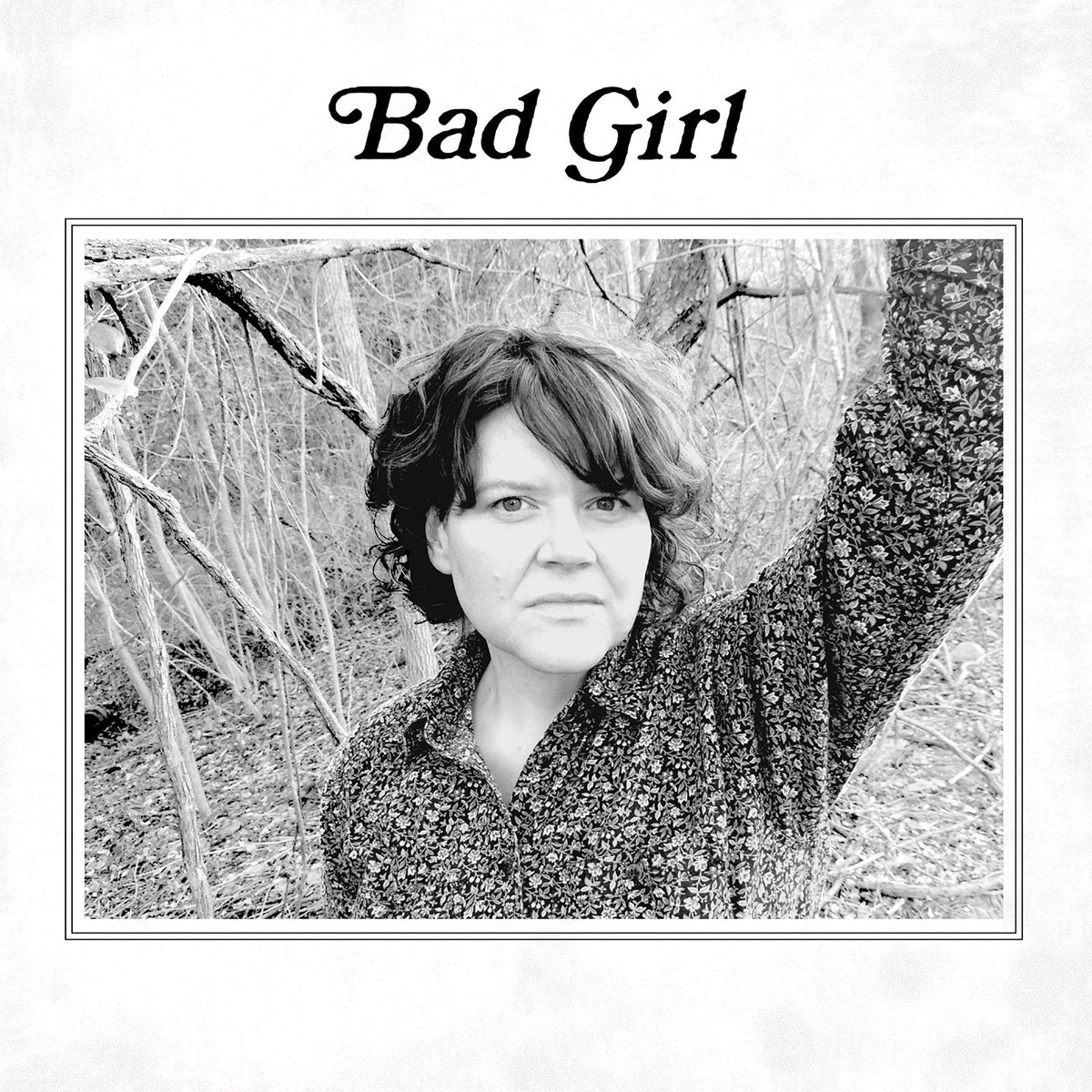

Reese McHenry & Spider Bags – Bad Girl LP Sophomore Lounge

$ 15,98 Original price was: $ 15,98.$ 9,59Current price is: $ 9,59.

Some artists wait for a great record to eventually come out of their efforts. Other records wait for their respective artists to become great enough to finally complete them.

In the mid-to-late ‘teens of our 21st century, with soundcloud, bandcamp, and a bouquet of social media outlets at the fingertips of just about any self-proclaimed “musician” in the western world, the speed at which we (singers, strummers, knob-turners, collectives, labels, and the like) are able to churn out recordings for whatever public will have them is currently at an unprecedented production rate. But even in these increasingly hurried times, not every record is suited for such land-speed – such is the case with Chapel Hill-based songstress REESE McHENRY’s debut full-length 12″ BAD GIRL.

When McHenry first began working on this batch of material with producer, co-songwriter, and key collaborator DAN McGEE (of fellow Triangle-area garage country cohorts SPIDER BAGS) over half a decade ago, the music scene acquaintances who merely admired each other’s rock n roll outfits from a passing distance (McHenry then the defining force behind Durham’s DIRTY LITTLE HEATERS) couldn’t possibly have known the gravity of the journey that lay ahead of their newfound friendship.

Gravity – it’s a word used with intention, in this case. The word that McGee uses to describe the very nature of the situation when McHenry first imparted him with the sentiment that, above all things, she wished to make a great record before she dies. Who doesn’t, right? The strummers, the knob-turners, we’re all searching for that. At least that’s how McGee initially took it. But as he soon came to realize, she meant something entirely more direct, more literal – perhaps, unfortunately, more time-sensitive than others. A victim of chronic heart problems (AFIB) and a series of strokes throughout the late-oughts, McHenry was deathly ill during the Heaters tenure, transitioning in and out of hospitals while continuing to work passionately on her music. In 2011, doctors severed half of her heart, replacing it with a pacemaker that helps it beat (and belt songs) to this day. Coincidentally or not, that was also the year she reached out to the Spider Bags in search of help with making this record.

At the time, Dan McGee’s production credits were hardly of note. Outside of his own music, he’d really only ever produced one record for friend and area musician Ben Carr’s band LAST YEAR’S MEN (a group of rowdy teenagers at the time with as much of a natural knack for mature and emotive narrative songwriting – brought to the surface, in part, with McGee’s assistance – as their inherent brand of balls-to-the-wall garage inferno). While he enjoyed the challenge and felt he had an ear for it, a wife at home, pregnant with his first child, and a band of his own to focus on progressing ultimately kept McGee out of other people’s studios. It wasn’t until McHenry approached him with the task at hand that he chose to revisit the roll of working on another person’s record. The rest, as they say, is history…

Well, eventually. Health and home-lives aside (if one can even divorce such nuclear matters), the making of the record itself came tangled with no shortage of obstacles. After all this woman had been through, there was inevitably a layer or two of rust that needed scraping. The Spider Bags (consisting of long-time percussionist Rock Forbes and somewhat new-comer Steve Oliva holding down the low end – both of whom, it’s worth noting, start to gel as SB’s definitive rhythm section over the course of these recordings) were no stranger to McHenry’s organic talent. What they were there to do was make her even better. To be her “house band,” like a Stax ensemble, catering themselves to the session without omitting their own recognizable charms. To write, arrange, and selflessly play, take after take, in service to the powerful, guiding tool that is McHenry’s voice and the 18-wheeled Peterbilt that is her spirit.

At the end of the day, Bad Girl is, by design, a singer’s record. In the traditional sense, with its considerate balance of material written by her, for her by others, and/or by others all together, the collection as a whole is offered to us, in song, by a modern woman faced with the every-day trials of love and growth, and the pains that mark their passing. From the album-opening title track, a gender perspective-swapping garage-wop take on Lee Moses’ timeless original, to the b-side’s soon-to-be American standard “Concrete Roses,” inked by McHenry herself and recorded live in one take – complete with Forbes masterfully playing brushes on a pizza box – without even having previously heard McGee’s arrangement for it (after the tape stopped rolling, everyone wept), there’s an almost cinematic quality throughout the long-player’s narrative. It’s the tale of a woman who tries her best to do good, to not be bad, but as we all know, life is rarely so black-and-white. It’s what she overcomes along the way that gives her color – that not only gives her a voice, but strengthens it by giving her something to sing. And if you ask me, or just about any schmuck from Chapel Hill to Hollywood, we’d be hard-pressed to find another protagonist as easy to root for as our very own Reese McHenry – singer, survivor, Bad Girl.

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

We offer a broad range of shipping options due to our long-running partnerships with UPS, FedEx and DHL. Our warehouse employees will pack all goods to our exacting requirements. Your items are carefully inspected and secured properly prior to shipping. We ship to thousands of customers every day from all over the world. This demonstrates our dedication to becoming the largest online retailer in the world. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders that contain more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

We will carefully examine all items before sending. Today, the majority of orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The expected delivery time will be between 3 and 7 days.

Returns

Stock is dynamic. It's not completely managed by us, since we have multiple entities, including the factory and the storage. The actual inventory can fluctuate at any time. It is possible that the stocks could be depleted after your order has been processed.

Our policy lasts 30 days. If you haven't received the product within 30 days, we're not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

To be eligible for a refund the product must be unopened and in the same state as when you received it. The item must be returned in its original packaging.